Nibi awan bimaadiziwiin

A collective of 2S Indigenous women water protectors seeking to increase support for the water in Hamilton Harbour through coalition building, information sharing and action.

November 2015. Hamilton activists Kristen Villebrun and Wendy Bush spent three days on a raft by the Waterfront Trail to draw attention to garbage including needles and tampon applicators that had washed up on the shore.

Floating “Protest” drew attention to sewage and related pollution in Hamilton Harbour

“It took us going out on a floating device and risking our health and safety, and it shouldn't come to that”

- Kristen Villebrum

-

Kristen Villebrun spent three days floating in Hamilton's harbour to get the city to notice how polluted it was. Then, she and Danielle Boissoneau spent three years pushing to get it cleaned up.

On a brisk, overcast afternoon at the Bayfront Park boat launch on Lake Ontario in Hamilton, Ont., Kristen Villebrun points to a dead muskrat that has washed up against a retaining wall separating the bay from walking trails. It’s the kind of thing most people don’t want to look at, says Villebrun, but it’s important that we do.

Most days, Villebrun, a petite, middle-aged Anishinaabe woman with flowing, chestnut brown hair, can be found walking the lengths of Hamilton’s waterways—from the Cootes Paradise marsh in the city’s west end over to Chedoke Creek, then on to Lake Ontario—pointing out things others would prefer to ignore. Like in the fall of 2015, when Villebrun and her friend Wendy Bush noticed scores of tampon applicators, needles and sewage washed ashore.

That day, Villebrun and Bush were building inuksuks—stone sculptures traditionally constructed by the Inuit, sometimes for navigation, sometimes as a warning—along Hamilton’s walking trails, near the harbour. Their goal was to spotlight Canada’s crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls, which the newly elected federal Liberal government had promised an inquiry into. That’s when they noticed the pollution.

Initially, Bush wasn’t sure what they were looking at. “It was like a big mat. It coated the top of the water, inches thick. It looked like clay almost,” recalls Bush, who is non-Indigenous. The more the women looked, the more debris and sewage they saw.

Villebrun and Bush say they alerted the city in late October, and that officials assured them there would be a sewage cleanup, but that weeks passed without one. City of Hamilton officials say the two got in touch in early November, and that a small cleanup was done within days.

What’s undisputed is that the women escalated their efforts to have pollution in the harbour taken seriously, and kept at it for years. Their activism would help uncover a sewage spill large enough to fill 10,000 Olympic swimming pools, an enormous amount that the City of Hamilton kept quiet for months.

In many Indigenous nations across Canada, women have a sacred relationship with the water—or nibi, as it’s called in Anishinaabemowin. In 2010, two provincial health centres commissioned Métis researcher Kim Anderson to explore this connection. To do so, she interviewed nearly a dozen First Nation, Inuit and Métis grandmothers, all of whom pointed out that water is essential not only to human survival, but the survival of all living things.

The phrase “water is life” has become a popular rallying cry at environmental demonstrations, but for many Indigenous women, it’s not a pithy metaphor—they see water as a sentient being with its own spirit. “Water is Mother Earth’s blood; her lakes, rivers and inlets are her veins, and all life needs water to sustain it,” Jean Aquash O’Chiese, an Ojibwe grandmother, told Anderson. Interviewees mentioned “Grandmother Moon,” as some Indigenous cultures call that astronomical body, which regulates the tides, while menstrual cycles, or “moon time,” roughly follow the moon’s 28-day cycle. Water features prominently throughout pregnancy and birth—it’s largely what cradles a growing baby, whose time to come into the world is signalled when the fluid-filled amniotic sac ruptures, known as when the water breaks.

As water plays such an essential role in women’s lives, says Anderson, many feel a sense of kinship with it. It’s a reciprocal relationship that requires giving thanks to the water for what it offers and accepting a responsibility to keep “the spirit of that water alive by ceremony,” as Cree grandmother Pauline Shirt told Anderson. One type of ceremony is a water walk, which is what it sounds like: mindfully walking around a body of water. Water walks are “education, they’re advocacy, they’re raising awareness about water,” explains Anderson. “It’s about developing a relationship with the water . . . reinforcing that relationship and the responsibilities we have to it.”

Perhaps the most celebrated water walker in Canada was the late Josephine Mandamin, an Anishinaabe grandmother from Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory on Manitoulin Island in Ontario. In 2000, Mandamin heard a prophecy that, by the year 2030, an ounce of water would cost the same as an ounce of gold. Three years later, at age 61, she co-founded the Mother Earth Water Walk, walking thousands of kilometres around gitchigami, or Lake Superior, to highlight Great Lakes pollution. Mandamin walked at least 17,000 km around waterways on Turtle Island, or North America, before her 2019 death. The many women who Mandamin inspired include her own great-niece Autumn Peltier, who has become an internationally recognized water protector. Still a teenager, Peltier is a regular speaker at the United Nations and has succeeded Mandamin as chief water commissioner of the Anishinabek Nation.

“There’s a teaching that grandmother Josephine used to give,” says Villebrun affectionately. “When you’re sick, and you go to the doctor, and you cough… when you see green, or yellow, you’ve got an infection, and you get medication for that. Well, the water is sick, it’s green, it’s yellow. It’s sick, and it’s showing us that.”

Back in 2015, she and Bush were fed up with what they saw as the City of Hamilton’s inaction on its sick water. Weeks after the women first noticed the pollution, they happened upon a piece of a dock floating freely. The two went home, collected warm clothes, charged their phones and returned to the harbour. They stepped out on the dock and floated into the harbour, staying there for the better part of three days. It was unseasonably warm for the middle of November. The women remember what Villebrun simply calls “death”: dead, bloated beavers, dead turtles, decomposed birds. “It was hard,” she recalls, holding back emotions.

But their bid to bring awareness to Hamilton’s waterways worked. Reporters showed up from CBC, CHCH News and the Hamilton Spectator. On the third day of their demonstration, Villebrun met with city officials, who agreed to close part of the waterfront trail. In mid-November, a cleanup crew protected by biohazard gear collected bags of waste filled with needles and tampons.

Wet weather can cause untreated waste water to be discharged into Hamilton’s waterways, says Dan McKinnon, the general manager of the city’s Public Works department. Heavy rain or melting snow can overwhelm the city’s infrastructure, causing underground tanks that are designed to trap and hold excess untreated waste water and stormwater to “bypass” and overflow. McKinnon says that in 2015, the city didn’t usually do cleanups after such discharges, because “we didn’t typically find a lot of [debris] on the shoreline.” He says a heavy October rainstorm that overwhelmed two of the city’s underground tanks may be to blame for the sewage Villebrun and Bush found in the harbour, but he can’t be certain. And even after the cleanup, debris continued to accumulate.

Villebrun shared her concerns with a friend, Danielle Boissoneau, who in turn organized the inaugural Hamilton Harbour Water Walk in 2016. Dozens turned out for the first of what is now an annual event. Water walks are “a beautiful thing,” says Boissoneau, an Anishinaabe mother of five, who finds the walks an invigorating way to connect with the water.

“Colonialism has done a really good job and not just on Indigenous people, but everyone,” says Boissoneau, who wants people to think of water as more than a resource or something to exploit. She considers water a living relative that enables human lives and therefore requires our protection. That most people don’t value it that way can be taxing on walkers. Many have fallen ill on the walks, including Boissoneau, who one year developed an upper respiratory infection and suffered sunstroke. “I think because we’re walking in such close connection to the water, we’re taking on some of the sicknesses and sadness that the water carries,” she says.

Two years after the water walks began, and almost three since Villebrun and Bush’s floating protest, city and provincial officials finally became alarmed enough about the water’s smell and high bacteria levels to warn its 537,000 residents about contamination in Chedoke Creek. An investigation was launched into the source of the sewage and, in July 2018, the city put out a release stating that a bypass gate on an underground overflow tank had been left cracked open, for unknown reasons. It had been found discharging untreated water into the creek. The release said that the city had immediately stopped the discharge and began the cleanup.

Six months later, according to the Hamilton Spectator, city councillors learned the shocking extent of the spill: 24 billion litres of stormwater runoff and sewage had been released into Chedoke Creek and the surrounding waters. The bypass gate had been open for four entire years. Yet neither the city nor the province informed the public of the amount or duration of the spill for months. In November 2019, prompted in part by the Spectator’s digging, Hamilton released formerly confidential reports about the open gate, the size of the spill, environmental assessments and possible cleanup options. Today, McKinnon from Public Works says it’s possible that the sewage and debris the women noticed in the fall of 2015 had flowed from the underground tank that was left cracked open in 2014. But again, there’s no way to be certain.

After news of the spill became public, Villebrun, Boissoneau and others came together as Nibi Awan Bimaadiziwin, a water advocacy collective of Indigenous women and two-spirit people. At a town hall meeting, the group urged city councillors to apologize for the sewage spill—not to them, but to the water itself. Boissoneau says it was a way of asking politicians to humble themselves and “learn about other ways of doing things.”

Three councillors agreed and, on the December 2019 winter solstice, accompanied Villebrun, Boissoneau and others on a trip to the waterfront. Boissoneau encouraged the politicians to take the opportunity to develop their own relationship with the water and showed them how to offer tobacco, a sacred Anishinaabe medicine given as a gift, to the water.

Nrinder Nann, councillor for a downtown ward, was there. She says the apology was a “deeply moving” experience. During hers, she made a commitment to “do right by the water.” She says the challenge for politicians facing public outcry was to avoid getting caught up in shame, and instead take responsibility. “It just felt like an opportunity to walk forward from that moment, instead of being in this place of defensiveness,” says Nann.

Since the spill, Hamilton has begun putting out a media release when the wastewater system bypasses and discharges sewage into Chedoke Creek. It also plans to hire more staff to monitor the system. The city is advising the province to simply monitor the creek, too, rather than dredge the bed, as recommended by an expert report from before the spill became public. (A more recent environmental consultant report, from this past February, suggested that dredging would only release more contaminants. That same report found that contaminants levels are now comparable to what they were before the spill.) In an emailed statement, the province said its investigation is in its final stages.

The city’s acknowledgement of the spill should have been a vindication for Villebrun. But it wasn’t, she says, because “the water is still sick.”

On one of her almost daily visits to the harbour, Villebrun steps out onto a boat launch. With one hand, she steadies herself against a railing. With the other, she sprinkles a pinch of tobacco. The shreds land on a thin sheet of ice covering the water. The dock shifts under her weight and water washes the tobacco away—as if to say miigwech, or thank you.

-

Two women vow to continue their floating protest on the waters of Hamilton Harbour until they get answers from the city about a tide of hazardous filth that has coated the shoreline next to the Waterfront Trail.

Kristen Villebrun and her friend, Wendy Bush, have been camped out on a small raft just off the shore about halfway between the Bayfront Park end of the trail and the Thomas B. McQuesten High Level Bridge since approximately 5 p.m. Saturday.

In late October, Villebrun and others began constructing a series of stone inukshuks along the trail to honour Canada's missing and murdered aboriginal women. Villebrun, 40, is an Oji-Cree woman.

She said when she first attempted to gather rocks to build her inukshuks, she noticed the shore was littered with used syringes, tampons and their applicators, plastic caps, condoms and feces.

When she called a city official, she was told there had been a spill of hazardous material from the sewage treatment plant at Woodward Avenue, which suggests the material had floated more than eight kilometres to the west from the Windermere basin.

Disgusted by the pollution and what they believed to be the city's inaction, Villebrun and Bush brought a small floating raft and some blankets late Saturday afternoon and decided they wouldn't leave until they got some answers.

The pair is also fasting, drinking only liquids.

"This is unacceptable," said Villebrun. "We're going to stay out here until we hear where this came from, what the source is and how they're going to clean it up in a timely manner.

"They've known about it since the 29th of October and I think that's enough time to get a plan set to clean it up."

The women said they're concerned for the safety of children and pets who might wander off the paved path.

"What happened to Hamilton being the best place to raise a child?" asked Bush. "There's needles down here, there's hundreds and thousands of Tampax applicators."

On Sunday evening, the city announced that in response to the women's concerns, the Waterfront Trail is now closed from the Bayfront Park boat launch to the high level bridge for cleanup. It is expected to reopen by Friday.

"The cleanup hasn't actually started yet but due to the type of waste, the trail is closed as a safety precaution," city spokesperson Kelly Anderson stated late Sunday.

She said staff is investigating the source of the waste.

Villebrun said she spoke briefly with city officials Sunday evening but vowed that the protest would continue until they actually witnessed the debris being cleaned up.

Ward 1 Coun. Aidan Johnson visited them Sunday afternoon and promised to help get answers. He was shocked by what he witnessed.

"It's disgusting," he said. "It's worse than I realized. There are used tampons, syringes, condoms and other forms of filth in layers all along the shoreline.

"Obviously a team that has some kind of expertise in biohazard cleanup needs to be tasked with the cleanup."

The women told Johnson there is similar hazardous contamination littering the shore of Princess Point further to the west.

Johnson said a quick examination of the shore suggested to him the material may have been the result of more than one spill.

"It looks to me like there are layers of debris. There's like an archeological phenomenon going on of layers."

Police have been checking in periodically with the women to ensure they remain safe. At one point, a police officer brought two life vests for them as a precaution.

Trail users have been stopping by to offer encouragement and one woman donated a case of bottled water and a container of coffee.

-

Hamilton Harbour Water Walks

Following in the footsteps of Grandmother Josephine Mandamin, water walkers have walked the 42 kilometres around Hamilton Harbour in ceremony to pray for, and celebrate, the continued power and resiliency of our most precious life source, water.

Since 1987, Hamilton Harbour has been listed as an "area of concern" by the International Joint Commission because of severe pollution and the continued degradation of water, mostly from industrial activity, sewage treatment plant effluent and urban run off.

In 2013, excessive phosphorous levels in Hamilton Harbour led to the "worst algae blooms in recent history." Phosphorous is a chemical found in fertilizer, detergent and animal feed. It makes it's way to the Harbour through waste water and poor storm water management. The ecosystems that thrive on the water in Hamilton Harbour are also suffering.

“We decided to do what we do best. That is to walk in the footsteps of our ancestors. As Indigenous women, we carry a specific responsibility to protect and honour the water. These are responsibilities that have been handed down intergenerationally through Rites of Passage ceremonies and our abilities as lifegivers. With these responsibilities in mind, we organized the Hamilton Harbour Water Walk on the Dish with One Spoon territory.

Hamilton is located on territory that has been historically shared between Anishnaabe and Haudenosaunee peoples. The agreement to share the territory was memorialized through the Dish with One Spoon wampum. The significance of the wampum is to illustrate our dependence on the land and water. The “dish” represents the land, the water and the abundance sustained by these life giving forces. The “spoon” is representative of our human activity, it is to remind us to be mindful of the ways in which we co-exist with the land, the water and all of creation.”

- Danielle Boissoneau

-

It was an early morning on the shores of Hamilton Harbour. A group of about 30 Indigenous and non-Indigenous allies gathered with a collective purpose. It was one based in love for the water, and somewhere deep inside, a dignified rage that fuelled our motivation to walk 42 kilometres in three days.

Two women from Hamilton approached me at the beginning of the year. “We have to do something,” they said. They were talking about the continued degradation of the water in Hamilton Harbour. The International Joint Commission (IJC) listed Hamilton Harbour as an Area of Concern in 1987. According to the International Joint Commission, an area of concern is a, “geographic area where human activity has caused, or are likely to cause impairment of beneficial uses of the area’s ability to support aquatic life, (1999).

Considering that 46% of the 45 kilometre shoreline is used for industrial purposes, (Bay Area Restoration Council, 2012), it’s easy to see how the water systems have become so denigrated. Randle Reef is located just west of US Steel and lies within the water of Hamilton Harbour. It has been deemed the “worst coal tar contaminated site in Canada,” (Hamilton Spectator, 2014). The International Joint Commission has scheduled Remedial Action Plans to help get Hamilton Harbour delisted, however, in the past, escalating costs has created barriers towards any implementation of these plans.

We decided to do what we do best. That is to walk in the footsteps of our ancestors. As Indigenous women, we carry a specific responsibility to protect and honour the water. These are responsibilities that have been handed down intergenerationally through Rites of Passage ceremonies and our abilities as lifegivers. With these responsibilities in mind, we organized the Hamilton Harbour Water Walk on the Dish with One Spoon territory.

Hamilton is located on territory that has been historically shared between Anishnaabe and Haudenosaunee peoples. The agreement to share the territory was memorialized through the Dish with One Spoon wampum. The significance of the wampum is to illustrate our dependence on the land and water. The “dish” represents the land, the water and the abundance sustained by these life giving forces. The “spoon” is representative of our human activity, it is to remind us to be mindful of the ways in which we co-exist with the land, the water and all of creation.

From June 15 to June 17, 2016, we embarked on a Water Walk, meaning that we would be praying for the water with our traditional medicines, our songs and our sacrifice. With support from community members in Hamilton and Six Nations, we were able to organize a fundraiser with musical talent being graciously donated by artists like Logan Staats, Piper Hayes, Sarah Beatty and Kahsenniyo. Because of this effort, we were able to raise $540, which covered nearly all associated costs!

Following in the steps of Anishnaabe grandmothers, like Josephine Mandamin and Judy DaSilva, we began our walk with songs and prayers. We were joined by all kinds of people. It was a heart opening experience to see how many kinds of people genuinely cared for the well being of the water. Young girls and young men began the walk, carrying the copper pot full of water as well as a water staff made by men from Oneida.

Leaving Bayfront Park, we began to walk eastward towards Hamilton’s industrial sector. The early morning start gave us incredible views of the sun rising over the Harbour. We were all kind of quiet as we started out. Bursts of laughter rang out every once in awhile, reminding us of our humanity and our ability to survive. Tobacco left our fingertips at every point that we seen or crossed the water. Soon enough, our views were blocked by monstrous industries spewing smoke. We were unable to see the water for many kilometres. We took a wrong turn, hoping to get closer to the water, and we ended up walking towards a fenced in property that let us know guard dogs were on duty. Shortly afterwards, Hamilton Port Authority became very interested in what we were doing and began to follow us and ask us what we were “protesting”.

A really great part of our Water Walk was the Sacred Fire that was burning the entirety of the three-day journey. Our firekeepers did a great job in helping to take care of our spirit and energy during this time. The first day, the fire burned at Bayfront Park. Many visitors came to sit at the fire to learn about what we were doing. The fire travelled around the Bay with us which was a really significant part of Hamilton Harbour Water Walk (Dish with One Spoon territory). The first evening of the walk, the fire came to join us at the first resting spot located on the shoreline of Lake Ontario.

The second day, we crossed the channel that separates the Harbour from Lake Ontario. With the copper pot and staff, we walked over a lift bridge that was created to make traffic on the water more accessible to the steel industry. During the late 1800’s the channel was dredged, which unsettled natural and unnatural sediments, to allow for transportation of products needed for, and created by, industrial activity on the shorelines of Hamilton Harbour.

From there, we began to lose sight of the water once again. Upscale neighborhoods and ritzy golf clubs stood in our way this time. Walking through Burlington, on the north side of the Harbour, was nearly as frustrating as the first day because it was really difficult to be able to focus on prayers for the water. We could see the water from behind gates but somehow I think this separation made the connection stronger because when we did get to offer tobacco, often it had been in our hands for a long time.

The second evening, we came to rest on the north shoreline of Hamilton Harbour. Our fire was carried from the shorelines of Lake Ontario to rest a second evening on the northern shoreline of Hamilton Harbour. Leaving from our final resting point the next day, it set in that we were nearly done. People in neighborhoods asked us why we were walking and when we told them, they encouraged our efforts. Cars passing by our small group of Water Walkers would honk their horns in support as we carried our copper pot and water staff. Everyone got to take turns carrying our sacred items during the walk. It was an inclusive and empowering experience.

Perhaps what made the Hamilton Harbour Water Walk most notable was the love and support from people. Many different kinds of people came together, all for the health and well being of our water. Many travelled from distances to participate, many friends spent all day cooking on Friday so that the Water Walkers could be welcomed back with a feast. Other Water Walkers joined us, many good conversations were had and new friendships made.

Upon returning home and resting for awhile, I came across some interesting, (and good!) news. On Friday, June 17, the day that we finished our walk, Catherine McKenna, Federal Minister of Environment and Climate Change announced a $139 million investment into the implementation of one the Remedial Action Plans designed to get Hamilton Harbour “delisted” as an Area of Concern. This particular plan is designed to contain the “toxic blob” known as Randle Reef. The project will have three phases and aims to be completed by 2022.

First, they plan to build a box to contain the blob, which is about 695, 000 cubic metres of toxic contaminants, coal tar and heavy metals. Randle Reef is 60 hectares and will require a containment unit as big as First Ontario Centre, three times over! A “double steel walled barrier” will contain the most toxic sediment. They hope for this phase to be completed by the end of 2017. The final five years will be spent between implementing the next two phases including the dredging of surrounding sediment which will be placed inside the containment unit. The third and final phase involves having the water removed from the containment unit and then placing an impermeable cap on top of it to seal the contaminants. (Hamilton Spectator, 2016)

It's great news that one of the Remedial Action Plans are finally being implemented but I don’t think that our work to protect the water will ever be done. Certainly not as long as industry, resource extraction and environmental genocide continue to be more important to Canadian society than the health and well being of our water, the land, the ecosystems and people who live closest to these places. While there is still much work to be done, our small group of Water Walkers is going to continue raising awareness of the continued denigration of Hamilton Harbour. With the help of Great Lakes Commons, we will be working in collaboration with Reclaim Turtle Island to produce a short video journal highlighting more of our personal experiences while on the Hamilton Harbour Water Walk (Dish with One Spoon territory).

We are continually grateful for our families, our friends and community members and those who demonstrate love for the water through actively defending our waterways and our lives. It is our responsibility to remind everyone that water is life. Everyday is a good day to be mindful of the miracle of water and maybe give some thought to what we can each do to help protect the water, even if it means just being grateful for it’s life giving qualities every time we use this precious resource.

Kchi Miigwech Kina Weya

Kchi Miigwech Nibi

-

Danielle Boissoneau wasn't in Hamilton long when she realized there were issues with the water.

Boissoneau moved here about 15 years ago, and took a walk along the Hamilton Harbour shore with her kids. They came across a bunch of dead, decomposing fish that had met their end without spawning. Her kids reacted in a big way.

"They yelled," Boissoneau said. "It startled me."

And that, she said, is "my first memory of Hamilton Harbour."

Boissoneau, who is Anishinaabe and lives on the west Mountain, will be one of the leaders in the Dish with One Spoon territory's Hamilton Harbour Water Walk today.

She and at least 20 others will embark on a 42-kilometre walk around the harbour. Everyone is welcome, regardless of race or gender. But Indigenous women, the traditional water keepers, are the driving force.

The third annual walk is a ceremony to pray for and celebrate water. Hamilton needs it, Boissoneau said.

The International Joint Commission has listed the harbour as an "area of concern" since 1987. While there's been significant investment and progress, the harbour's water quality still suffers under the weight of sewage effluent, run off and industrial pollution.

'It's really very crucial right now': Great Lakes Water Walk focuses on protecting 'lifeblood'

In the past, Boissoneau has carried the copper water pot and staff on the ceremonial journey. It begins at Bayfront Park around 6 a.m., and finishes around 3 p.m. in the same spot. There will be a sacred fire, and a feast.

"For me, it's kind of atmosphere where the hair on my skin stands on end," she said of the walk. "It's really beautiful and phenomenal."

Lynda Henriksen of Hamilton will be there too. Water is tied to health and life, she said.

"Safe and clean water and its connection to our lives is so strong," she said. "We have to have respect for her. We have a responsibility of stewardship."

What have I done for the water today?

Why lakes and rivers should have the same rights as humans | Dr. Kelsey Leonard, Indigenous Water Scientist

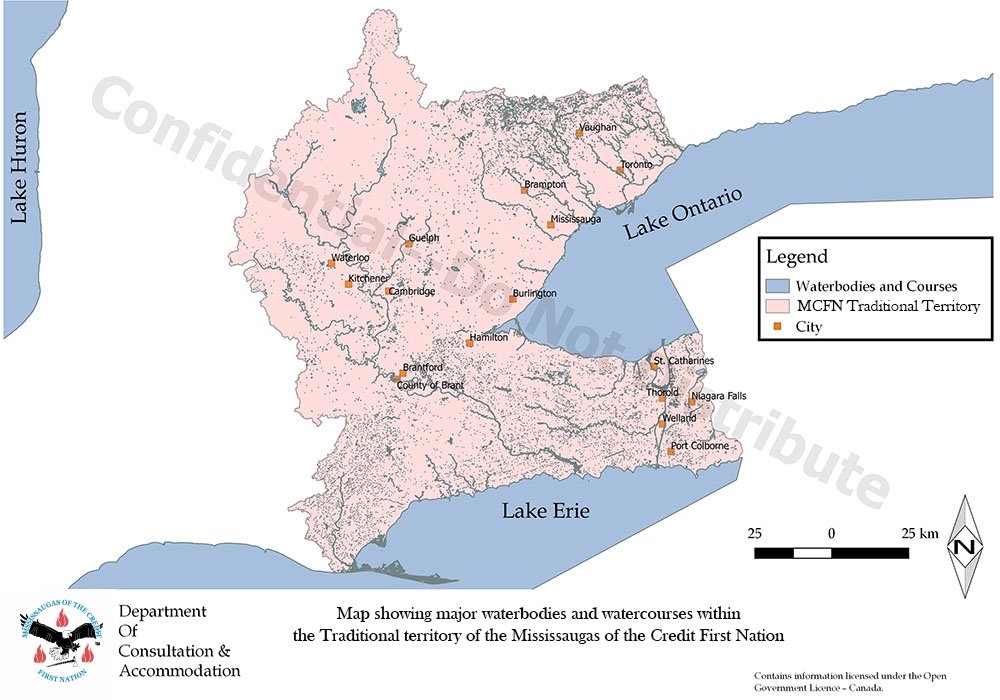

In September of 2016, the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation filed an Aboriginal Title Claim to Waters within the Traditional Lands of the Mississaugas of the New Credit. Our people continue to revere water as a spiritual being that must be accorded respect and dignity. Water is also vital to the survival of the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation and all other forms of life.

As stewards of the lands and waters, we advocate for a healthy environment for the people and wildlife that live within our treaty lands and territory. The Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation remains committed, as we have been for generations, to utilizing, protecting and caring for the waters in a holistic way that promotes continued sustainability. We want to maintain and strengthen positive relationships with the people who share our treaty lands and territory.

The Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation asserts that we have unextinguished Aboriginal title to all water, beds of water, and floodplains contained in our 3.9 million acres of treaty lands and territory. Read more here.